According to the Eleventh Circuit, the cost-shifting provision of Rule 68 is mandatory such that if the judgment obtained is less than the Rule 68 offer, the offeree must pay the costs incurred post-offer the district court does not have the discretion to rule otherwise. And since costs are properly awardable only to the “prevailing party” under the Copyright Act, an accused infringer who receives anything less than a defense verdict is not entitled to fees under Rule 68. These circuits rely on the Supreme Court opinion in Marek, and in particular the Marek Court’s interpretation of the term “costs” to mean all costs properly awardable under the relevant substantive statute or other authority.” The reasoning behind this position is that costs are recoverable only if they are “properly awardable” under the relevant statute. The majority view-held by the Seventh, Ninth, and First Circuits-is that a defendant in this situation may recover his post-offer costs, but may not recover post-offer attorneys’ fees, as he is not the “prevailing party” under the Copyright Act.

The various circuits seem to agree that a plaintiff in this situation could not recover its post-offer costs or fees, because it did not obtain a judgment more favorable than the Rule 68 offer-but what about the defendant? The circuit courts also appear to agree that a defendant may recover its post-offer costs under such circumstances, but what about its attorneys’ fees? Does Rule 68’s cost-shifting provision allow the defendant to recover its post-offer attorneys’ fees, as well as costs, for receiving a more favorable judgment than its offer, even though it technically is not the “prevailing party?” The answer to this question depends on where a case lies.Īs noted above, the circuit courts are split on the issue. § 505 permits the court to award attorneys’ fees to the “prevailing party” as part of the “costs.” So what if the plaintiff technically “prevails” on its copyright claim by proving the defendant’s liability and obtains a judgment for $10,000, but that judgment is less than the defendant’s pretrial Rule 68 offer of $25,000? But what happens when the underlying or substantive statute-like the Copyright Act-also includes “prevailing party” language? For example, in copyright infringement cases, 17 U.S.C. The Supreme Court has made clear that when Congress expressly includes attorneys’ fees as part of the costs recoverable under a statute, those fees are subject to the cost-shifting provision of Rule 68. Yet, the circuit courts are divided on the specific application of the cost-shifting provision of Rule 68, particularly in the context of substantive statutes that only award attorneys’ fees to a “prevailing party.” The following discusses application of the rule to common intellectual property litigation cases, which all involve different substantive statutes or governing law – copyrights, patents, trademarks, and trade secrets. The Supreme Court has interpreted Rule 68, and particularly use of the term “costs” therein as all costs properly awarded under the relevant substantive statute or other authority, which means all costs properly awardable in an action are to be considered within the scope of Rule 68 costs. For refernce, the text of the rule is reproduced at the end of this post.

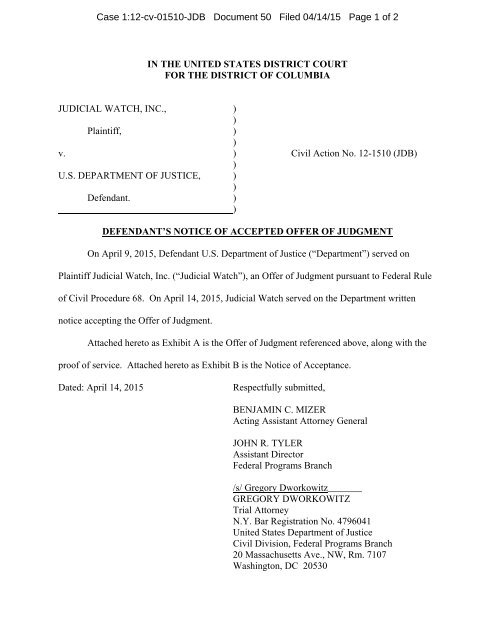

#OFFER OF JUDGMENT TRIAL#

1 (1985), “he rule prompts both parties to a suit to evaluate the risks and costs of litigation and to balance them against the likelihood of success upon trial on the merits.” In other words, if the defendant believes the plaintiff is over-optimistic about its prospective recovery, it may call the plaintiff’s bluff. As noted by the United States Supreme Court in Marek v. The plain purpose of Rule 68 is to encourage settlement and avoid litigation. If the offer is not accepted and the judgment finally obtained by the offeree is not more “favorable” than the offer, the offeree must pay the costs incurred after the making of the offer. The Rule provides that if a timely pretrial offer of settlement (made no later than 14 days before trial) is made and accepted, a judgment is entered against the defendant according to the terms of the offer.

Rule 68 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure is somewhat of a hybrid between a settlement and a decision on the merits. Introduction to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 68 “Offer of Judgment”

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)